How to make your terminal nicer to use

I mentor a lot of junior developers, and it makes me sad to see so many stuck with the ugly, hard-to-use default terminal setup their machine came with. As a developer you probably spend a large chunk of your day using it, so it’s a good idea to invest a little bit of time in making it look prettier and work more like a modern application.

It can be overwhelming looking at power users’ configurations since they tend to have years of accumulated stuff, and little explanation for what everything does. This guide will keep things as minimal as possible—just setting up a few useful things. If you dump 200 cool aliases and plugins into your setup you won’t even remember most of them are there and they’ll never get used.

A little computing history

I got a little carried away here so feel free to skip this section if you’d rather get straight to the configuration.

Using a terminal to control your computer feels unnatural and different at first. This is because to a certain extent they are relics from the past.

What is the terminal?

Way back before Graphical User Interfaces (or GUIs) were invented a terminal was a separate piece of hardware that let an operator interact with a computer that probably filled an entire separate room.

Operators would use a textual interface to enter commands and interact with programs and files on the computer. These are known as Command-Line Interfaces (or CLIs).

Eventually computers were small enough to fit under a desk, and came with GUIs. However although graphical interfaces were good at letting new users discover features, they were slower for experienced operators. If you know exactly what you want to do and the right commands to do it a text-based interface can be faster and more powerful.

So computers came with “terminal emulator” programs that allowed the use of CLIs. The default Terminal.app that comes with a Mac is an example of a terminal emulator.

What is a shell?

Operating systems have what’s called a “shell” (often more than one). This is the bit at the edges of the system that the user interacts with. For example you can think of Mac’s Finder & Dock or Windows’ Explorer & Start Menu as the graphical shell.

Terminals also have a shell—this is the set of commands and language features you can type to interact with the computer. Nowadays most Unix-like operating systems use Bash or Zsh as their command-line shell (this includes Mac, Linux, and Windows if you’re using WSL).

The shell is what you interact with when you type commands into a terminal. When you enter ls the shell interprets the command as “list the files in the current directory”, accesses the storage drive to read all the file names, then prints them to the terminal.

All popular shells descend from a common ancestor, which is why most commands and syntax work whether you’re using Bash, Zsh or Fish.

Configuring your terminal

Enough history, let’s make our terminal useful. Most of the shell configuration applies to any operating system (since the shell is the same). However the terminal stuff is specific to Macs since that’s what I use (sorry).

First I recommend installing a better terminal emulator than the default. macOS’s Terminal.app is perfectly adequate, but it’s less configurable and modern than some alternatives. iTerm is the most popular—it’s super configurable and has great performance. You may also like Hyper, which is built with web technologies and therefore easy to customise with JS.

iTerm

I use iTerm, with a few customisations. The most important is switching to “natural” text editing. This makes all the normal keyboard shortcuts work in the terminal (e.g. cmd-left to jump your cursor to the start of a line, option-delete to clear a single word etc). Otherwise you’re stuck with whatever ancient keyboard shortcuts were used for text editing in the 1980s. You can change this by going to Preferences > Profiles > Keys > Presets... > Natural Text Editing.

You probably also want to bump up the font size considerably, since most terminals assume you have a 480p CRT monitor instead of a retina display. You can change this in Preferences > Profiles > Text.

I’d also recommend installing a nice colour scheme. You can find these online: they’re files with a .itermcolors extension. I’m currently using Dracula. Install them by navigating to Preferences > Profiles > Colors > Color Presets... > Import.

Configuring your shell

This is where things get really interesting. The shell is responsible for pretty much everything you see and everything you can do, so it’s worth making it your own.

Using a modern shell

I highly recommend you use Zsh as your shell. It’s the default on Macs as of macOS Catalina, and it has a lot of nice features over something like Bash (which you may be using). Check which shell you’re using with:

echo "$SHELL"This should print something like /bin/zsh or /bin/bash. If you’re not using Zsh you should install it and switch. On a Mac Homebrew is the easiest way to do this:

brew install zshThis should automatically switch your shell over (you can check with the same command above). If it doesn’t switch (or you install Zsh another way) you can change your shell using chsh and the path to your Zsh install:

chsh -s /bin/zshZsh settings

You can configure your shell with a config file, which usually lives in your home directory. Bash is configured with a .bashrc file and Zsh with a .zshrc file. These are “dotfiles”, which are hidden by default on most systems. Check if you have an existing config file by listing everything in your home directory:

ls -a ~The -a makes it list all files (including hidden ones). If you don’t see a .zshrc file listed create one with:

touch ~/.zshrcOpen the file using the text editor of your choice. I use VS Code, so I can open it with:

code ~/.zshrcIf you already had a config file it might have some settings in it. Feel free to ignore this and append stuff to the bottom—you probably won’t break anything. If you’re really worried make a copy of this file to your desktop before you change it:

cp ~/.zshrc ~/Desktop/zshrc-backupNow we can start configuring our shell.

Changing your prompt

The “prompt” is what shows up on the line where you’re entering commands. It “prompts” you to enter a new command. Bash shows a $ by default; I think Zsh shows a %. You can include much more useful information here however.

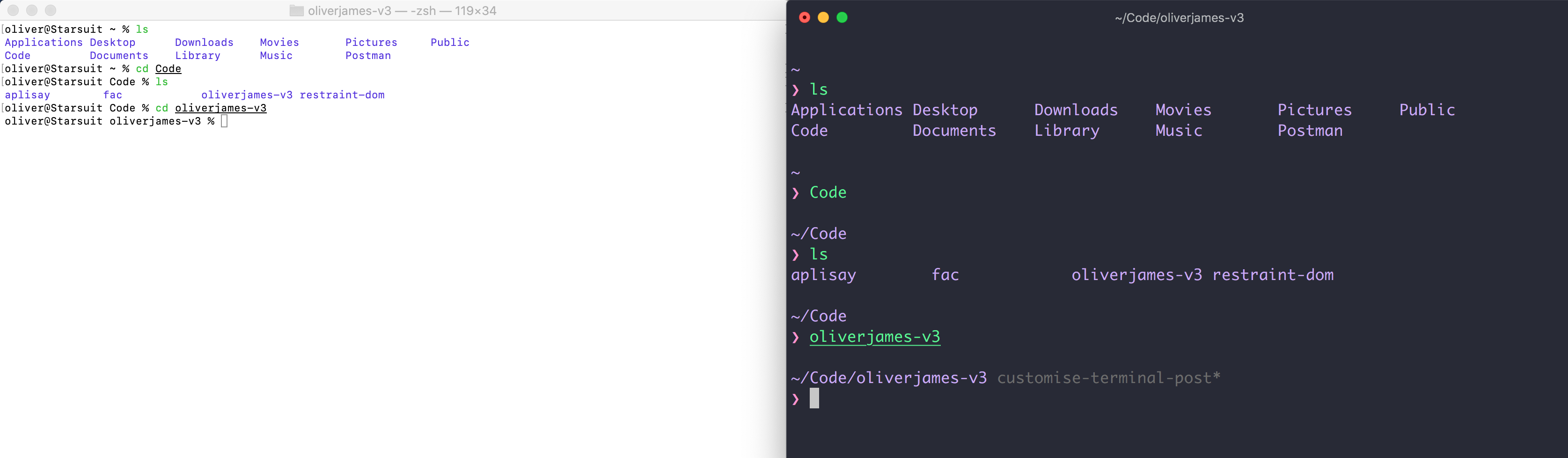

You can see my prompt shows the current directory, the current git branch and whether I have un-committed changes (the asterix). I’m using Pure Prompt. The easiest way to install this is with npm:

npm install --global pure-promptYou can then enable the prompt by adding these lines to your config file (.zshrc or .bashrc etc):

autoload -U promptinit; promptinit

prompt pureThere are other more elaborate prompts online if you’d like something more intense.

Auto cd

Zsh has some cool features that you have to enable. The first is “auto cd”, which allows you to change into a directory by just typing its name. E.g. instead of cd my-code you can just type my-code. This also allows you to move up a directory by entering just ...

Add this line to your ~/.zshrc and save the change:

setopt AUTO_CDFor this to take affect you have to either restart your terminal or run this command:

source ~/.zshrcThis will run the settings file and pickup any new additions.

Set your default editor

Lots of programs force you into a text editor at certain times. For example when git needs you to write a commit message it automatically opens your default editor. This is usually Vim or Nano, neither of which are intuitive. It’s nicer to stick to your usual editor, which for me is VS Code. You can change the default by adding this line to your ~/.zshrc:

export EDITOR="code -w"Substitute whichever editor program you prefer on the right-hand side.

Autocompletions

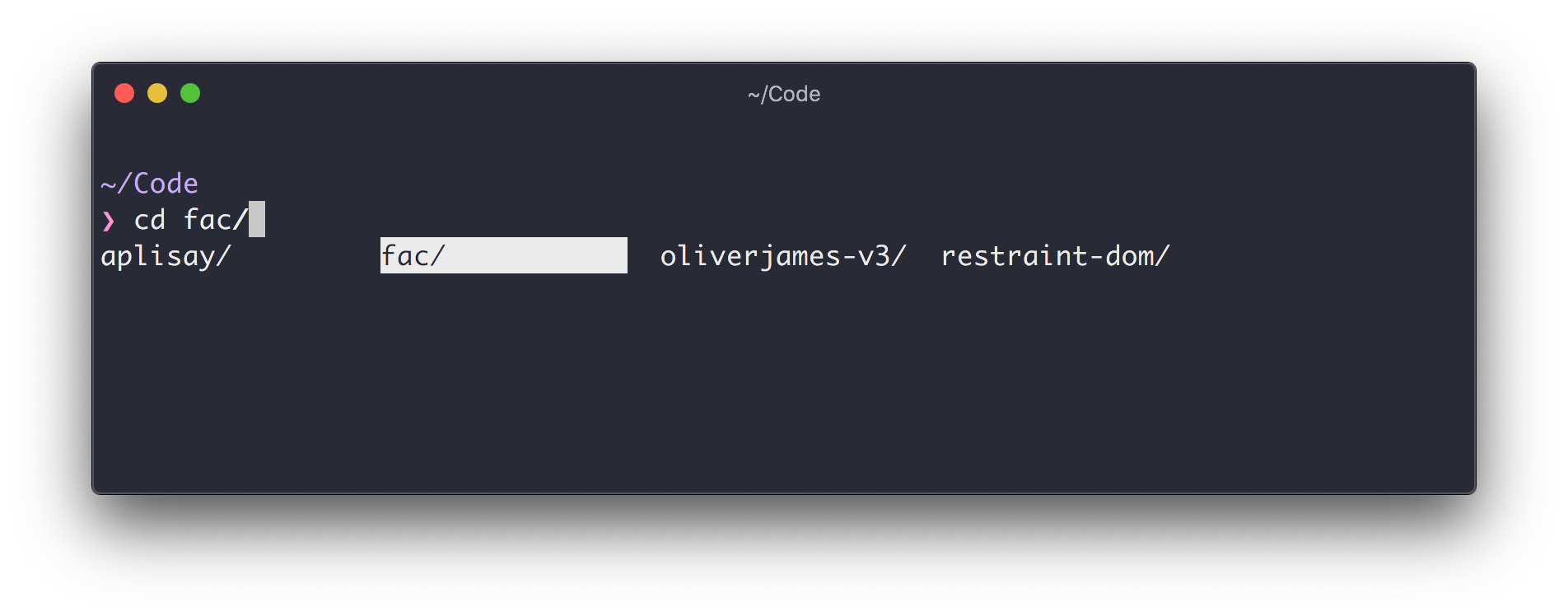

Zsh has really nice built-in tab-completion. For example if you type the start of a directory name and hit the tab key it’ll show you the possible matches and let you hit tab to move between them.

To get a nicer visual selection menu you need a bit of config. Add the following lines to your ~/.zshrc:

# initialise nice autocompletion

autoload -U compinit && compinit

# do not autoselect the first completion entry

unsetopt MENU_COMPLETE

unsetopt FLOW_CONTROL

# show completion menu on successive tab press

setopt AUTO_MENU

setopt COMPLETE_IN_WORD

setopt ALWAYS_TO_END

# use a pretty menu to select options

zstyle ':completion:*:*:*:*:*' menu selectAliases

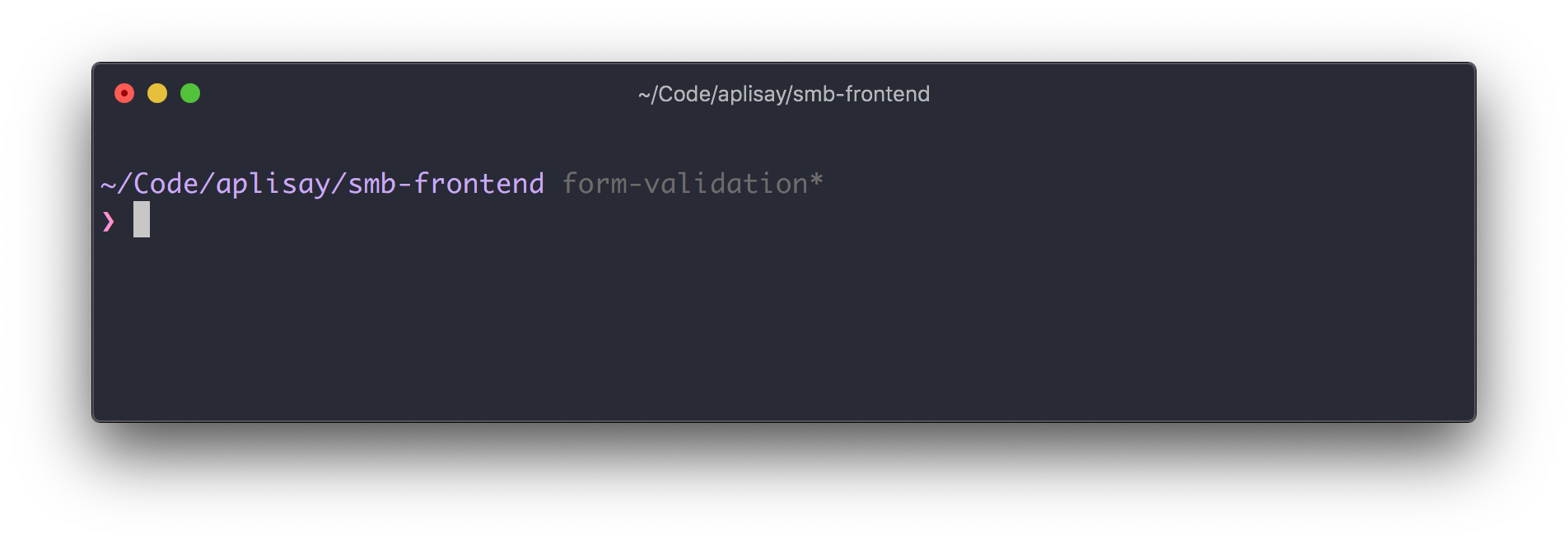

Aliases let you create shortcuts for stuff you do often. For example I often work on this website, so I have an alias configured to quickly switch to that directory:

alias jam='cd ~/Code/oliverjames-v3'You can add as many of these as you like to your ~/.zshrc. I have a whole bunch of git ones for common tasks:

alias ga='git add'

alias gst='git status'

alias gl='git pull'

alias gp='git push'

alias gc='git commit -v'

# and many moreYou can even use aliases to override default commands, for example to make ls always show a coloured output:

alias ls='command ls -G'My favourite aliases are for quickly moving up a directory:

alias ...="../.."

alias ....="../../.."

alias .....="../../../.."This lets me enter ... to move up a two directories, .... to move up three etc (assuming you have auto cd enabled).

Functions

Zsh also lets you create custom functions. By far my most used is mkcd. This lets me create a new directory, then immediately move into it:

function mkcd() {

mkdir -p "$@" && cd "$_";

}I also have a function for quickly setting up a new JS project:

function newjs() {

mkcd "$1" && npm init -y && git init && npx gitignore node

}This will create a new directory, create a package.json, initialise git and add a gitignore.

Summary

Here’s everything we added to the ~/.zshrc again all together:

setop AUTO_CD

export EDITOR="code -w"

autoload -U compinit && compinit

unsetopt MENU_COMPLETE

unsetopt FLOW_CONTROL

setopt AUTO_MENU

setopt COMPLETE_IN_WORD

setopt ALWAYS_TO_END

zstyle ':completion:*:*:*:*:*' menu select

alias ga='git add'

alias gst='git status'

alias gl='git pull'

alias gp='git push'

alias gc='git commit -v'

alias ls='command ls -G'

alias ...="../.."

alias ....="../../.."

alias .....="../../../.."

function mkcd() {

mkdir -p "$@" && cd "$_";

}

function newjs() {

mkcd "$1" && npm init -y && git init && npx gitignore node

}Hopefully this has helped you make your terminal a little more useful. If you want a little more inspiration you can see how my setup is configured in my dotfiles repo on GitHub.